![]()

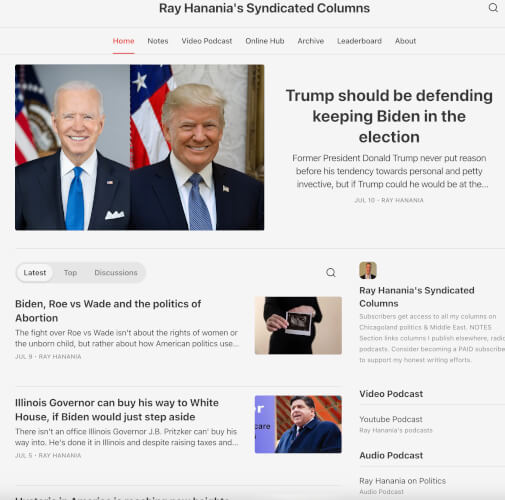

Midnight Flight: Chapter 4 — Written Long Before

One family’s experience of White Flight and the racial transformation of Chicago’s South Side (an online novel)

By Ray Hanania

Midnight Flight, (C) 1990-2019 Ray Hanania, All Rights Reserved

Chicago’s borders, literally, marked the end of civilization as we knew it.

Beyond the city’s borders was a vast wasteland of forests and farmlands. Corn, cows and overalls. In the suburbs, they actually called Levi jeans “overalls.” People didn’t dream about building a suburban home. When they wanted to go to the “country,” they went to Brookfield Zoo.

But here we were, the Hanania family, pulling up in front of a “ranch style” home in one of Chicago’s near southwest suburbs.

In less than a year, in 1968, our cozy community of South Shore Valley had found itself pulled apart. Ethnic diversity that seemed to touch finger tips there, broke apart radically with each group headed in different directions to a different suburb. Human nature is to scatter wildly when you are running from something rather than running toward something.

Suburban life, for us, was a culture shock. It did not start out as innocently as it might have for other families and neighbors who sold their homes for reasons other than the fear that their next door neighbor would be “Colored.”

Wall of former Henry Hart JCC along Jeffery Avenue, 2017

Years later, when asked, many of these refugees from White Chicago would offer a wide range of excuses to justify their flight to the suburbs.

Some moved into the suburbs seeking a better standard of living, more space, better schools, a refuge from Chicago’s intense Ward politics and the Machine’s demanding precinct captains. You wanted a garbage can lid, the precinct captains wanted a vote. And, they were at your door nearly everyday at the behest of their aldermen or committeemen. Mayor Richard J. Daley was forging Chicago’s infamous Democratic Machine and our parents were its main vassals.

Others moved to find better jobs, even though they ended up driving back into the city in heavy, lengthy, rush hour traffic congestion. During those tediously long drives, they must have reminisced about why they left and the homes that they left behind.

I did and still do. I wonder what it could have been like to stay. I have often driven back through my old neighborhood, cruising slowly past my old house. Unchanged. Still attractive. Still vibrant. It survived.

Why couldn’t I?

The truth was, most people who fled from the city’s South Side did so to escape a nightmare vision of racial turmoil, fed by the media, fueled by the uncertainty of the times, and prodded along to protect what was left of their treasured “nest eggs.” Fear drove them, not reality.

Some homeowners stayed, braving the community’s fears of the unknown. Many said, years later, they were glad they did. I believe them.

My family and many families that lived near us fled because we were running from fears stoked by money-hungry Real Estate speculators who saw huge profits in the home fire sales created by inciting racial fears and panic-peddling. People were running not just because they feared an invasion of Black people into their neighborhoods, but, more importantly, because Realtors had managed to exploit racial fears to augment an even greater fear, the fear of losing equity that had been gained in their homes. Home equity was the one area where personal wealth had seen a dramatic rise following World War II and the baby boom that followed. People ran because they were led to believe — easily — that they would lose the value in their homes. A “stampede” atmosphere had taken place that turned normally rational thinking, blue-collar workers into apparently irrational race-mongers.

That ugliness remains as I look back at this past.

It didn’t become the “old neighborhood” until we left. The neighborhood was idyllic and still is. The trees were huge and arched over the streets, creating cavernous thoroughfares, and still do.

The only thing missing were the people who had once enjoyed it, fleeing in an era of growing racial tensions and concerns. Author, former neighbor and friend Lou Rosen describes it as being like a neutron bomb exploding, erasing all signs of former human life, but leaving the buildings, farms, trees and cars all intact and undamaged. Unchanged. That is exactly what it was like.

Whether by design or by accident, society was moving in a direction that accommodated the decision of many White homeowners to run with their fears behind them, rather than to confront them and stay where they were at.

After we left, we all found ourselves stuck in the “suburbs” a community concept whose creation actually beckoned White homeowners to leave their city homes and abandon the racial climates there with promises of the “real American dream.”

Suburban growth was an inevitable development, that began, almost like an experiment, with the creation of a G.I. Town in August 1948 called Park Forest.

Park Forest was built to accommodate World War II soldiers retiring from military service. The suburbs offered winding roads and a new concept in dead-end streets called “cul-de-sacs” to allow mothers working in their kitchens to keep tabs on their children playing in centrally located “tot yards.”

Most of the discharged soldiers were White.

To accommodate the expected new suburban populations, the first bi-level commuter trains were launched on Sept. 6, 1950 on the Aurora line of the Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad.

Most of the commuters, who enjoyed this new service, were White.

Although the goal was to settle millions of new baby boomers into a sprawling suburban network, the suburbs didn’t really start to blossom until the end of the sixties, just about the same time that Realtors were recognizing the dramatic profits that could be made from orchestrated “White flight.” In fact, statistics show that even though the population of the Chicago area grew by only 4 percent between 1968 and 1990, the suburban sprawl doubled in size.

What happened wasn’t population growth. It was population movement. And it was by skin color. People were “running from” not “running to.” Something other than “living room” was motivating people to leave the comfortable surroundings of their homes and move to the suburbs.

Chicago began plowing through miles of old neighborhoods, laying millions of tons of concrete and asphalt, to create new expressways such as the Congress Street Expressway. The Congress Street Expressway divided the world into two parts, north and south, plowing from the Lake on the east straight west. The ribbon cutting took place on December 15, 1955, several months after Chicago inaugurated the first flights from the newly opened O’Hare Airport which served to encourage increased suburban business investment and increased land values in what had previously been vast tracks of difficult to reach farmland.

Although it was denied often by the city’s politicians, some noticed that these new expressways seemed to coincidentally create difficult-to-breach divides between White and Black neighborhoods.

The expressway was completed in 1960 and four years later, it was renamed in honor of former World War II General and former President Dwight D. Eisenhower. It was suitable, if you imagined the expressways as generals in a war to keep the races apart.

Sports was a significant and high profile part of American life. It was very visible. And the advancement of Blacks into Sports was noticeable to many Whites, and many of them resented it.

On Sept. 22, 1959, the Chicago White Sox won the American League Pennant, defeating the Cleveland Indians on their home turf. They were known as the “Go-Go” Sox, boasting a 94-60 winning season. And although the sport was open to people of all races, most of the attendees were White, too. The Pennant victory was a “White” celebration.

Most sports was still “White” sports, although Blacks had viewed sports for generations as one of the few avenues left open to them for upward economic mobility. Resistance to their participation was open and historic. Baseball had, at one time, in the late 19th Century, banned integrated baseball leagues. It wasn’t until 1945 that Jack Roosevelt Robinson became the first Black player to play for a Major League team, when he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers He didn’t play until 1947. He dominated on the playing field, despite name-calling, racial epithets, and a black cat being thrown at him during a game in Philadelphia.

By the 1960s, much had changed, although Black baseball players complained, rightfully, that they were not getting the same fair treatment as Whites. Few White colleges recruited Black baseball players, and few Black colleges had baseball teams. From 1960 through 1971, Black players were limited on team rosters by their position, with most confined to the Outfield, First Base or second base. They were considered “untrustworthy” as pitchers or catchers.

The first Black man didn’t play on an NBA team until 1951 when the Boston Celtics signed Chuck Cooper. In golf, Robert Lee Elder didn’t become the first Black man to play in the Master’s Tournament until 1975. Yet, more than 20 years later, the country club that hosted the Master’s Tournament only had one Black member.

In football, Marion Motley became the first Black to be inducted to the National Football Hall of Fame in 1968.

The 1959 White Sox Pennant victory was also the beginning of one of the first real scares in the City of Chicago.

That night, to celebrate the White Sox victory, Fire Commissioner Robert J. Quinn ordered fire sirens to sound for five minutes. Coming late in the evening, many people feared that the siren finally marked the beginning of a new war with the Soviet Union and their rambunctious Communist strongman, Nikita Khruschev. Months earlier, Khruschev threatened to bury the United States under a hail of nuclear missiles.

The White Sox later fell to the Los Angeles Dodgers four games to two, losing the World Series. But despite that loss, the Chicago White Sox continued to symbolize the enthusiasm and camaraderie of Chicago’s White community.

While government thought of ways to help the White middle class and the rich, they could not totally ignore the poorer Blacks who migrated to Chicago from the South. These Blacks came to Chicago and other Northern cities hoping to escape segregation and its underlying racial hatred, only to find a different kind of discrimination, one that wasn’t so open or acknowledged.

On March 5, 1962, Mayor Daley inaugurated the nation’s largest public housing project, handing a bouquet of flowers to a glass inspector and father of two children at the Robert Taylor Homes. The goal was to replace dilapidated old housing stock of the inner-city with these newer high rises. Large sections of the city’s black neighborhoods were scraped up and replaced with the towering buildings that became magnets for the poorest of black and minority families.

It didn’t raise the standard of living of the Black community, but it did help keep them all together.

The 50s and 60s were times of uncertainty and change with many unforgettable moments and days.

One of the most unforgettable moments occurred on November 22, 1963. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated and nearly everyone can tell you exactly where they were at or what they were doing at the moment they first heard the shocking news. I was walking up the hill of the school playground, returning from lunch, when a friend yelled to me, “Did you hear? The president was assassinated.”

Like a lot of the problems of our times, it wasn’t racial. But it certainly contributed to the inner-sense of uncertainty that fed into the impending racial conflicts.

On Sept. 5, 1964, the Beatles performed to a packed audience at the Amphitheater on their first visit to Chicago. It was another major day celebrated by the city as a whole, one enjoyed almost exclusively by the White community. I got in to see them perform with friends. I didn’t see any Black faces at the Amphitheater. Black rhythm and blues remained in doors, in the dimly lit night clubs and off the major Sunday night TV programs.

Oh there were a few Black pop singers. But they didn’t seem Black at all. Chubby Checkers and the Twist was a White phenomena, or at least it seemed. Mom would drive us to the Community Discount Store at 87th and Greenwood. And, we’d enter the Twist dance contests while buying cheap, discounted shoes and clothes for school. Or, we’d enter the hoola-hoop contests and win Beatles records.

We collected 45 rpm records and played all the songs off the WLS Radio Silver Dollar Survey. That’s the only survey that you would want. There were comic books and teen magazines. And lots of bubble gum to chew.

South Shore Valley lived the 60s to its limits.

But there were the nightmares, too.

It is often said that people are murdered not by people of other races, but by people of their own race. Black’s kill Blacks. Whites also killed Whites.

And in the summer of 1966, a White drifter and ex-convict walked into a student townhouse on East 100th Street and Luella Avenue in Jeffery Manor and committed one of the most spectacular and horrendous murders of the decade. It certainly was the worst event that had occurred in our community, ever.

The bodies of eight student nurses were found in their living quarters, brutally raped and murdered.

The mass murder suspect sported several tattoos including one on his left arm that read “Born to raise hell” and another on his knuckles that read “Love/Hate.” He was White.

The killer’s name was Richard F. Speck, 24, a sailor fired from his ship who went on a drinking binge only days before the killings, after losing his job. One nurse, whom he overlooked, had survived the slaughter. She had hid under a bed and watched as a drunk and drugged up Speck raped and murdered the other young nursing students, one at a time over the course of several hours. She identified Speck to police by describing in detail his array of tattoos. After seeing TV reports that he was wanted for the murders, he attempted suicide and was taken to a hospital where a nurse recognized his tattoos.

The event was ghastly. Every grisly detail was reported vigorously and repeatedly by print and TV reporters. Newspapers bannered shock headlines that scared people. His face was blown up on the front page of several papers. Sinister looking. Dark. Different.

Although it wasn’t a racially inspired killing, it was a shock to the city and even more so to our community because the killings occurred so close to where we lived.

There seemed to be this belief that somehow, crime did not occur in the suburbs. It only occurred in Chicago, and usually as a result of racial strife. The Speck murders only added to this misconception.

But there were events in the Black community that did reach heights of significance, too, and that affected all of us.

On Friday, August 5, 1966, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., led a march through one of Chicago’s most identifiable White enclaves, Marquette Park. He was confronted by thousands of jeering and angry White protesters, a mob really, chanting and hurling epitaphs, calling King “that nigger.” They waved placards that read “King would look good with a knife in his back.” As he led his march to protest segregation and racism in Chicago, a rock hurled by an unknown White assailant had struck King’s head.

Rather than embarrass, it caused many Whites to come together in their feelings of animosity and fear.

Under pressure, King agreed to end his demonstrations when the Chicago Real Estate Board agreed to terminate its policy of fighting open housing laws. Both endorsed, instead, a “fair housing ordinance” introduced to the Chicago City Council to guarantee the rights of blacks to buy homes anywhere in the city. That did not sit well with either community.

Many blacks denounced the agreement as a “sell out” by King. For Realtors, it marked a definitive moment and the start of their drive to whip up White homeowners into a frenzied “White flight.” For White homeowners, the King confrontation in Marquette Park only made it easier to believe that Blacks would soon be moving to their neighborhoods too, and next door to their homes.

Television was filled with images of violence and graphic war reports from a faraway country called Vietnam.

These broadcast reports helped make it easy to accept the notion of a war. It was a war, after all. Although in the mid-60s, nightly body-counts continued to shock many Americans.

We didn’t hear much about Vietnam in the early 60s, but that changed dramatically by 1967 and 1968. Little by little, one at a time, young men were disappearing from our neighborhoods. Homes were starting to display the little banners in their windows indicating that their family had a son serving in the armed forces, or, more tragically, that their family had lost a son in the faraway war in Southeast Asia.

It wasn’t until LBJ was nearing the end of his term that TV seemed to become more and more filled with images of the war. Soldiers fighting the Communist horde in a country that few of us knew. In school, the plays addressed the issues of nationhood and I remember being tapped by the teacher to play a person from Siam. I think we had someone play Laos and Cambodia, but I don’t recall anyone playing Vietnam.

It was a sore point, it seemed.

We didn’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about it, that is, until one of the older boys was drafted and the mother put a small blue banner with a star in her window. These little flags started popping up all over the neighborhood and that Halloween in 1968 there seemed to be a lot of the banners in a lot of windows.

One of my friend’s parents built a small underground bomb shelter in the back yard of their home. It created a large lump in their yard and had a metal door that opened at ground level to a staircase to the inside of the shelter. He was not allowed to bring anyone in there. The canned food they stored there, electronic equipment like a TV, radio and a portable “burner” to cook food, were valuables his parents did not want stolen.

Not everyone built one, but they were there.

The Vietnam war fueled an anti-War movement that further exacerbated tensions. Rich White students were dodging the draft, while poorer Blacks were being drafted in huge numbers. Good grades in college would provide a deferment. But, if you were Black and didn’t attend college, you were scooped up by the draft board and sent to basic training where they prepared to ship you off to killing fields thousands of miles away. So turbulent were the times and the protests, President Lyndon Baines Johnson announced on March 30, 1968 that he would not be a candidate for election.

He walked away from a country that was torn both by racial strife and anti-war protests. His walking away also left many people with a sense of hopelessness. JFK wouldn’t have walked away, some said.

The racial fuse was lit, and heat was coming from every corner. But it did not really ignite until late on Thursday, April 4, 1968. Standing on the balcony of a Memphis motel, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., was shot dead by an assassin, later identified as James Earl Ray. What many expected to be a quiet weekend had suddenly turned into a series of ugly riots and mob clashes with police that spread through the city. To aggravate the circumstances, schools closed early. Teachers at Joseph Warren Elementary school had gathered all the kids together at lunch time and announced that school would be closed early and they should go straight home.

My sister, Linda, had come home telling us that her teachers told students not to come back to school after lunch, “And to stay inside their homes and to lock the doors.”

Bowen High school also was closed early, although many of us were not allowed to go to school that morning by our wary parents. Uniformed and fully armed units of the Illinois National Guard were patrolling Stony Island Avenue and 87th Street where some teenagers had thrown large rocks through the windows of businesses there. Some car windows were smashed. Fences were kicked down. But people actually expected something worse, like a Black military invasion, or something.

Throughout the city, Schools were being closed, sending thousands of young teens, in particular, loose on the streets. These teenagers reacted to the rising emotions that they witnessed firsthand in the homes of their parents where Black people were far from admired. Martin Luther King’s name was often taken in vain. The release of students early no doubt contributed to the escalating violence that swept the city.

The Eisenhower Expressway had served as an easy by-pass for White motorists around predominantly Black inner city neighborhoods. On this Friday evening, however, angry black teenagers ran through the rush hour jammed expressway, breaking windows on cars and hurling rocks at their drivers. The black communities on the city’s West Side exploded in flames as Blacks took to the streets. Whites, seeing this frenzy, and fearing that Blacks “gangs” would come to their neighborhoods, formed impromptu and special community car patrols. These unarmed patrols cruised the streets late into the evening alert for strangers and Blacks whom they feared would bring their rioting from the crime ridden inner city to the tranquility of all White city neighborhoods.

The Black inner city had erupted into riots. Buildings were left to burn because firemen feared going into the Black areas to battle the fires. Smoke billowed from the burning buildings throughout the Black communities. The scenes of burning buildings and heavily armed Chicago police filled our TV screens. It certainly put a scare not only into the minds of many White homeowners in our community, but also frightening, probably more so, middle class Black families who also feared the escalating violence that occurred around them.

Mayor Daley ordered Chicago police to “shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand … and to shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting any stores in our city.” Blacks and Whites were doing the looting, although if you were to ask any White person that day, they would have insisted that only Black people were looting.

As if not wanting to be left out, Hollywood released in 1968 the first in a five-movie series called Planet of the Apes. Based on a 1963 French work entitled The Monkey Planet, it told the story of a society of talking and civilized apes that dominated Earth in the distant future discovered by three astronauts whose ship had gone awry. Man had evolved into a species of mute, work animals, while Apes and Chimpanzees had taken over the planet. Man was subjugated as pets and served as mules who did the menial work. The movie series openly touched upon social issues like discrimination, paralleling the experiences of Blacks with that of the monkeys.

Naturally, that sparked a debate about the symbolism and the attempt to parody society’s exploding racial tensions. The idea that a society of Apes could rule the world was presented as science fiction. In a sense, although the comparisons were not positive, the movie suggested that similar contentions that Blacks were more superior to Whites was science fiction, too.

In school, many White kids renamed the movie, “Planet of the Niggers.”

That summer, Chicago erupted into more violence when blue-shirted Chicago Police officers, assigned to protect the Chicago Democratic Convention, lost control and targeted convention protesters. Described as a “police riot,” tensions increased. Somehow, many people associated the left wing hippies with the leaders of the same civil rights movement that threatened to undo the years of investment many Whites had made in their neighborhoods. The protests at the Convention were only peripherally concerned with racial and civil rights issues, but the event only further added tension to an already tense White society.

The news media had begun to shift from newspaper print coverage to live reports broadcast on local radio and television. The racial hatreds and the protests went from being distant events reported in newspapers, to uncomfortably close conflicts brought right into your front-room compliments of your television sets. It was right there in their homes.

We watched the weekend long funeral of JFK on the TV. We watched as Jack Ruby walked up to Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, and placed a pistol to his stomach. He shot and killed him live on the TV, too. The riots after Kings death filled our TV screens. And when Robert Kennedy was gunned down in California, in the summer of 1968, we saw the spectacle replayed over and over again on television.

Sonny and Cher were pushing the hippy generation onto the crowded boob tube, later holding hands with daughter Chastity — a name that also taunted traditions — and they sang a song that promised they would stay together forever, “I Got You Babe.” Of course, sometime in the late 70s and 80s, they got divorced, like everyone else in America.

In December 1969, eight armed police officers under the direction of Cook County State’s Attorney Edward V. Hanrahan entered a two-flat on Chicago’s West Side, guns blazing. The headquarters of the Black Panthers at 2337 West Monroe Street became the site of a seven minute long gun battle, with police doing all the shooting. Two Black Panther leaders, 22 year old Mark Clark and 21 year old Fred Hampton, were left dead.

In the midst of this social upheaval, a black family of four moved into a home on 89th Street and Luella Avenue, several houses north of where I lived.

It was a seemingly small event, compared to the larger events that exploded in society around us. Certainly, it was undeserving of notice.

But for many White homeowners in South Shore Valley, it symbolized the very essence of the menace that they saw in society’s troubles. It was at that moment that the turmoil of the 60s moved from graphic TV news reports and images to a real life, in-your-face drama.

For South Shore Valley’s White homeowners, most of whom were tranquil and peace loving people with no personal animosities toward Black families, that was the event that changed their lives.

Midnight Flight

Chapter 3: A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

Chapter 4: Written Long Before

Chapter 6: Alone in the Playground

Chapter 8: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 10: The Sub-Urban Life

Chapter 11: Friends Left Behind

Chapter 13: Notes from Readers