Midnight Flight: Chapter 3 — A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

One family’s experience of White Flight and the racial transformation of Chicago’s South Side (an online novel)

By Ray Hanania

Midnight Flight, (C) 1990-2020 Ray Hanania, All Rights Reserved

“You don’t know, what we can find.

“Why don’t you come home with me little girl,

“on a magic carpet ride?

“You don’t know, what we can see.

“Why don’t you tell your dreams to me,

“can’t you see we’ll set you free?”

— Magic Carpet Ride

Steppin’ Wolf, 1967

When it really comes down to it, it’s not just where you live but who you happen to live with.

I knew every neighbor on my block and across the street. I knew kids and families all over, between our home and Joseph Warren Elementary school. As a kid, I could freely come and go into other people’s homes.

There was a trust. It was familiarity. They knew me. I knew them. And that’s what made the feeling of “safe” come alive for all of us.

In the early days, South Shore Valley defined what “safe” was for many homeowners. That sense of safety is what defined everything. It put meaning in our lives.

As a young child, my best friend was the girl who lived just next door to me on the south, Sharon Zurek. A few months younger than me, Sharon and I were always very close. Her mother, Frances, was a nurse, which suited her because she was such a gentle, kind and caring person. I guess our closeness had something to do with the neighborhood but also the fact that her mother was divorced. She was one of the first divorced parents I or my parents had ever met. So naturally, there was this feeling that my parents had to take Sharon with us everywhere we went, to picnics, to the beach, and to the movies.

Sharon and I sang the lyrics to Beatles songs together, played with hoola-hoops that we swung around our hips, but more often held vertical to the ground and threw away from us with an inward spin that caused the hoola-hoops to roll right back into our hands.

We’d listen to the radio all day on Saturday, and on weekday evenings to radio DJs like Larry Lujack. WLS and WCFL were warring radio stations and their competition was a part of the times. We carried little plastic encased radios and plug little earplugs into the side to listen. They ran on batteries and we would have them all the time. A little wheel on the side would change the channel. There were only two we cared about. WLS and WCFL.

We would buy our small, vinyl 45 rpm records from a music store, a record shop, on 87th Street near Stony Island. That’s where we would get our copies of the Silver Dollar Survey. I Want to Hold Your Hand was a song we sang together the first time I tried to give her a kiss. The kiss wasn’t so much sexual as it was a challenge to youth. Of course, the moment I leaned over as we sat on her front steps and I kissed her, my dad happened to walk out of the house and he yelled to me. He startled me so much, I must have turned white.

Sharon remembers me giving her a kiss at the playground, my mouth full of black licorice.

To raise money to buy the records, we’d collect and save pop bottles. It was a big deal because you could turn in dozens of bottles and make some good change. I think the records cost about 65 cents each.

The record shop was near Gwon Lee’s carry-out restaurant which was owned by another close friend, Catherine Lee. Cathy was the first Asian person I had ever met. Cathy first started at Warren Elementary school in 3rd grade.

The fact that she was Asian seemed to bother a lot of people, and she experienced a lot of discrimination, looks, stares, taunting and many rude and inappropriate comments about her race. But, I don’t recall looking at her experience as a racial problem, even though it was. It just seemed more haphazard, and there were a lot of good moments.

A few houses to the north lived another friend, Helen Pomerantz. I only knew her for a few years. Helen had died at a very young age.

“Helen had a weight problem, maybe an illness associated with it, I’m not sure,” Sharon recalls.

“We’d go over to play with her and we would have a blast working on little handicrafts and puzzles and coloring. And when I would get up to go home for dinner, or something, her mom would come up to me and say, `Thanks for playing with Helen.’ It was like no one would come and play with her and I played with her because she was such a good friend.”

Across the street were the McCarthy’s. They had a large family and a lot of children, including a boy my age, Michael. Michael died at a young age, also. He was swinging from rope that he tied to the basement ceiling over the stairwell. He slipped or the rope broke and he fell, cracking his head open on the steps.

We weren’t allowed to go to the funeral. It had been the same when Helen died, too. One day, she was just gone.

We lived on the block and the block was the extended home. We knew everyone and everyone knew us.

As I got older, my “boundaries” changed and included blocks around our block. There, I met many more friends.

But it was the same process.

I think I lived at Jack Stone’s house, and also with Jeff Brody, Michael Rothman and Sheldon Asher. I’d eat dinner with them, and sometimes they’d eat dinner at my house, although we were a little poorer than they were.

But, since none of us lived in Pill Hill, we all considered ourselves poorer than a number of other kids.

Pill Hill was rich. Every place else, wasn’t.

There was also a certain style to how people dressed that reflected a lot of your ethnic and social characteristics.

My friends bought their clothes from Mr. D’s clothing store on 87th Street, a few blocks east of Stony Island Avenue. There also was a barbershop nearby where my Jewish friends would get their hair cut for $3.75. I’d go with them and watch. The barber would give them a small “duck tail” in the back, which most of them preferred.

Your hair cut did reflect your religion, purely by coincidence. Duck tails became fashionable in one community. The Christian kids sported “box cuts.”

I wore a “box cut” although I always wanted a duck tail. But my mom cut my hair, and hence, I would always receive the easy to cut “box cut.” It was all she could muster, other than making sure my hair was cut evenly around my ears and off my eyes.

I wanted it over my eyes, because that’s how The Beatles and other rock and roll musicians were styling their hair. They spent hours combing their hair and using a blow dryer or their sister’s curling iron. I had never heard of one yet.

No matter how hard I tried, the hair over my eyes kept curling. It wouldn’t straighten out in that flip that Paul McCarthy wore all the time. It just curled.

You even got to the point where you started to see differences in people’s hair. The Jewish kids had straight hair. The Christian kids had curly hair. Maybe that’s why they used VO5. I don’t know.

If you were Eastern European or Arab, you wore socks that had mixed colors and patterns. You also wore black shoes. The Eastern Europeans greased back their hair, too. Products like VO5 were heavily advertised on our black and white Television sets.

I don’t know why. It’s just what everyone did.

With slicked back hair, the Greasers also wore dark clothes, gray and black jerseys and black leather shoes that came to a near point and that rose above the ankles. During gym class, they would wear the obligatory gym shoes and white shorts, but they would never take off their solid black or multi-patterned black and gray socks. You could usually pick them out of the crowd, easily.

If you were Jewish, you wore “cordovan” Penny Loafers with a dime or a penny wedged in the front flap. You might also wear a blue pullover V-neck sweater with no shirt or only a T-shirt underneath. You also wore Levi jeans, a new, popular clothing style for boys. But, you didn’t wear socks.

As the world moved into the beginnings of the psychedelic generation, the hipper kids started to emulate the hippies wearing CPO jackets with lapels, “Granny” sun glasses (from Granny in the Beverly Hill Billies and Grace Slick, the lead singer from Jefferson Airplane). And, if you were cool, you also wore Gant shirts with “lucky loops” on the back. The Lucky loops were yanked off the shirts and collected by the girls – it was expected and desired, even though it might cause a small rip in the back of your expensive shirt. Girls in our school would walk around with large collars or lucky loops in their hands.

There was a casual relationship between the boys and the girls, although sex was something we only talked about as if we were more wishful than experienced.

Boys and girls didn’t really date each other, but they did go steady. Well, they went steady for about a week. Then, they broke up and went steady with someone else. The boys would wear a gold or silver bracelet. Depending on how much money you had to spend and where you lived was reflected in whether the bracelet was gold or silver, or how thick it was. You gave it to your girlfriend when you went steady. And you took it back when you broke up.

Pleading, I finally got my mom to buy me a bracelet, very thin and only silver-coated with my name engraved on the band. Of course, it never went anywhere, and didn’t look so cool when I was comparing it to the ones my friends had.

You didn’t buy Gant shirts at Goldblatts Bargain basement where mom would take me to shop in South Chicago. Still, you could find clothes that were passable.

I went to the JCC pool as the guest of my friends nearly every summer day where we lounged poolside and watched the girls in their skimpy bikinis. We talked about sex, pot and parties. We all worked and spent a lot of our money at poker games held in the basements of the homes of friends like Lou Kagan, Art Wittert, Jeff Brody, Phillip Resnick and Danny Gingold. Resnick and Gingold lived in Pill Hill, the preferred place for a good card game where as much as $200 changed hands.

Jack Stone and I each bought Folk guitars and learned to play guitar together. (Eventually, I became a prolific Rock and Blues guitar player in my later high school days.)

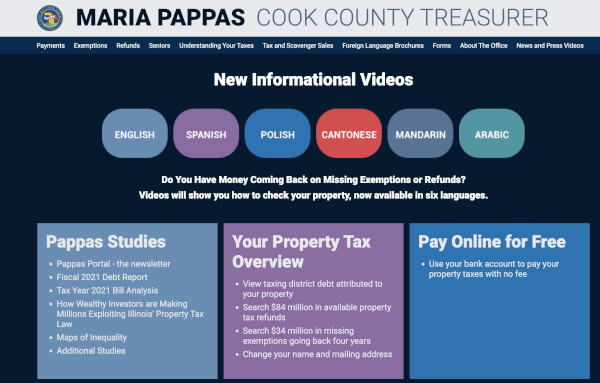

I took lessons on guitar. My sister played piano on an upright Wurlitzer. My guitar instructor was Hispanic, Bruce Quintos. Today, Quintos is an officer in the Cook County Forest Preserve District. Each week, I’d walk to his house at the corner of 91st and Luella carrying my guitar. He’d teach me new Jazz guitar techniques. Lessons were tedious and boring, until one day I convinced him to pause in the lessons so we could watch Herman’s Hermits perform Mrs. Brown You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter during a television appearance, I think on the Ed Sullivan Show.

That’s what I wanted to learn. That’s what he said I didn’t need to take lessons to play. “Real guitar is a little more sophisticated and it takes real talent. That other stuff is easy.” Easy or not, that’s what was popular.

Quintos had me enter a Music Competition held at Jones Commercial High school in the Loop and made me play a song called Dock of the Bay by Otis Redding. I won first place. It happened that it was one of my first and very few encounters I had with Black kids. They were everywhere that summer when I went to Jones and they all looked at me like I was some kind of a geek. I wonder how many of them had encounters with White kids. We just walked passed each other, staring.

But Jazz wasn’t where we were at, as kids, although it helped me build up my skills as a lead guitar player.

Jack and I would go to his home on Paxton and play the lick to Secret Agent Man and also Wipe Out.

It seemed that every time we would leave the JCC Pool and walk down Jeffery Boulevard, we would detour and pause at the big window at Markons Deli. There was a large table for six people situated at the window where people dined and looked out onto Jeffery Boulevard. We’d each take turns and walk up to the window, pull down our pants and flash our “puds.” The startled diners, usually elderly ladies, just looked at us like we were nuts. We always checked to make sure none of our parents were at the table, though.

South Side Jews were tough.

They seemed to have a bad image among the Christians I knew. Most of the Christian kids hated them and always wondered why I hung around with them. I didn’t understand the hatred. They were my friends. They were always good to me and we stood by each other as friends.

Once at a card game at Lou Kagan’s house, Steve Kagan accused his cousin of cheating. Lou got upset and started yelling back, throwing the cards on the table. There must have been $35 in the pot, which was pretty hefty for that day and age and for kids who were in their mid-teens, only. Art Wittert, who was one of the taller and huskier kids, and who had dropped out of the game, was reading my hand with me. Wittert stood up and declared, “Hey, you can’t do that. Herman, here, has a full house. He wins!” Kagan yelled back at him and Wittert hit Kagan so hard he flew across the family room. Wittert scraped up the winnings and Kagan’s cash and gave it to me.

Afterwards, he complained, “You know, South Side Jews are real pussies.”

I said that I knew a number of Arab kids, too, and thought they weren’t too tough either.

“No. You know the Ali kids, don’t you?” he asked.

“Yea. I know them real good.”

“They’re tough Arabs,” Wittert said.

In the summer of 1968, before I moved, we often would take the bus or drive to Rainbow Beach on the East Shore.

Although Rainbow Beach was far from a “rainbow,” it was an eclectic collection of White people. There were only a few Hispanics. Blacks didn’t go there. They weren’t wanted.

It was the only place outside of school where I would see both groups of my friends, Jews and Christians, hanging around with each other. They didn’t socialize together, otherwise.

I got a job two years before at a Burger King restaurant that was owned by an Arab friend of my family. I wasn’t old enough to work but he hired me anyway. I made 95 cents an hour and ate all the Whoppers I wanted. Later, I went to work at Jewel Osco at 87th and Stony Island Avenue.

Some of my Jewish friends were hired there to, but I noticed that the employee base was divided socially and religiously.

We were hired as “bag boys.” We were a part of the Union and we were paid well, I think about $2.75 an hour. But the job that paid the best money and that had the best hours was the position of grocery stock-boy. It paid about $2 more an hour.

Eventually, some of my greaser friends said they were going to get me promoted to stock-boy, even though a few of my Jewish friends who bagged groceries with me had been at their jobs longer.

“We don’t promote Jews. We won’t work with them.”

And sure enough, I got promoted and my Jewish friends didn’t.

Here we were, I thought. Worried about Blacks moving in the neighborhood, when the real hatred and animosity was right there, under our noses. Of course, that Jewel did not hire Blacks as stock-boys or grocery baggers. There were a few Black women who worked the cash register, I think.

Even after moving to the suburbs, I still kept the job for a while. It was a long bus ride, but I had good benefits and great pay.

Eventually, one of the supervisors heard me complaining about why some of my Jewish friends had not been promoted to stock-boy. He told me to shut up and “do my job.”

I shut up.

But as stock-boys, we worked evening shifts when everyone else was gone, unloading large pallets of grocery stock and putting them on the shelves. All the labels had to be lined up with their labels face outward. The placing of groceries was meticulous, but tedious and we’d talk to each other over the aisles as we worked, and I again, asked, why Jewel didn’t promote any of my Jewish friends to stock-boy and why they always remained as baggers. As we worked, we were allowed to take pop and chips to drink and eat while we worked. We didn’t have to pay for them. It was supposed to be one of those unannounced privileges that went along with being a stock-boy.

But the supervisor came up to me and asked me if I paid for the chips.

“No. But, we’re allowed to.”

I looked around at my friends who were pushing their bags of chips aside, out of view. I thought, maybe, someone would speak up. But no one did.

He fired me on the spot.

“That’s what happens when you stick up for Jews,” another friend told me as I left.

I was kind of relieved. Traveling to the East Side to work was a pain, after we moved west. And, that was the last time I had to see any of those “friends” again.

Midnight Flight

Chapter 3: A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

Chapter 4: Written Long Before

Chapter 6: Alone in the Playground

Chapter 8: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 10: The Sub-Urban Life

Chapter 11: Friends Left Behind

Chapter 13: Notes from Readers