![]()

Midnight Flight: Chapter 11 — Friends Left Behind

One family’s experience of White Flight and the racial transformation of Chicago’s South Side (an online novel)

By Ray Hanania

Midnight Flight, (C) 1990-2018 Ray Hanania, All Rights Reserved

Rely on memory for inspiration, but always check it for perfection and accuracy.

Memory is human. So, it is not infallible. I also know that my experiences are not necessarily the experiences of others. And, my interpretations of events may not always agree with the interpretations of others.

It is important to add the views and feelings of others, not necessarily to be merged into the context of this book that reflects my perspective and experiences. But in a sense, their views and feelings should be offered somewhat independently to preserve the context and the feelings that reflected their experiences of the social atmosphere of the late 60s, White Flight and the events as they unfolded.

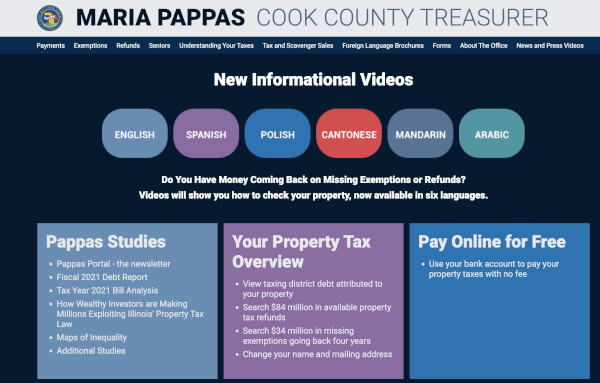

Typical home of a friend on 90th Street near Luella Avenue

Here are a few of those feelings:

Sharon Zurek’s story

Owner, Black Cat Productions

Sharon Zurek was born in June 1953. She was a few months younger than I was. She was my next door neighbor living on Luella Avenue, living most of her life there until she was 23. She moved out on her own in 1976. Her mother, Frances, stayed for many years after that.

Whenever I think of the South Side, I always go back to being 5, 6 or 7. And the thing I always remember was that all the kids could play till late at night in the summer time. Late to us was 10 p.m. It was all about feeling safe. I don’t think I have ever felt like that since, but I think that is the world in general, today. A lot of it was you and Linda. The whole big deal was what are you going to do? I don’t know what I’m going to do.

Our world, at first, was our block. But as we got older, it expanded to other blocks. But it never went further than the neighborhood.

The big scary thing to me was the viaduct. Getting through the viaduct to the other side, to 95th Street, was a big deal. Like the viaduct kept us apart from the other side, what ever was there.

That’s what I missed the most, though, the feeling of “a real neighborhood.” But while we knew the kids, it wasn’t like our families got together and had picnics. The families were somewhat isolated. Our neighboring families always went places together. But I don’t remember families even across the street doing things together.

That was different for the kids, though. We all did get together.

Ethnicity, and racial and religious identity were evident. People back then knew who was Catholic. Everyone knew who was Jewish. Everyone knew who was Polish. They knew who was Italian. It was like your ethnic background was important. But it didn’t seem to stand in anyone’s way. And no one reacted to the idea of ethnicity the way they reacted to being Black.

The safe thing is about a feeling. It’s not about color or race, really. It is about an environment and the world. We felt safe. We felt like we didn’t have to worry. It wasn’t about being safe from other people, but feeling safe in our neighborhoods. It was in our heads. We talked about the boogie-man. It wasn’t a real thing. It was a make believe monster. But our world today is full of so many people who do bad things … it is not a color thing. It is an evil versus good. I miss the safety of being naive in the 50s and 60s. It wasn’t always a White thing versus Black thing. It as about feeling that you could leave your door unlocked.

Even if our neighborhood had remained all white, the times had changed. And the times were more threatening to everyone, not just because of race. Not because who lived there, but because of the world out there.

I was attracted to the Black kids because they were different. In grammar school, I didn’t feel that I had connected to anyone. Cathy Lee was my best friend since 3rd Grade and she was the first real ethnic to move into our neighborhood. I always hung out with the people who were outsiders.

They came form somewhere else. And what was that like? I never got a chance to figure it out.

While I didn’t know everything about Lee Bogan and Michele Demby, I knew everything about Cathy Lee. I practically lived at her house. I was there all the time. Maybe that was a difference. We mixed but we didn’t really mix. I never went to their homes and they never came to my home.

From 8th grade to high school, it was a time of transition so it softened the blow a little because the high school had more Latins and some Blacks, although it was predominantly Black.

The thing at high school that did happen was that people were more segregated. The Spanish Kids hung out by themselves. The Black kids hung out by themselves. The White Kids hung out by themselves. It wasn’t until King was assassinated that we saw something different.

I remember the day King died. In the school cafeteria, all hell broke loose. Plates were flying. Food was flying. Chairs were flying. Kids were yelling and screaming. But it happened all around me. I didn’t want things to change. I was going back to get my 5 cent deposit back on my bottle and Cathy was yelling at me to get out, asking me what I was doing. There were fights and confrontations in the cafeteria. The school sent us home early and we poured out of the school. The worst thing the school did was to let all the kids out. It just added to the commotion and the fights.

In high school, I was in honors class and the Black kids I knew were in those classes too. They were just smart. I didn’t look at them as Black, I looked at them as smart. And I admired that.

Cathy Lee’s Story

Cathy Lee’s family moved into South Shore Valley in the 3rd Grade, about 1960. She attended Joseph Warren Elementary school, graduating in 1967.

Her father and mother were born in the Canton area of Southern China. Her father served with the US Army during World War II before permanently settling in the United States. He opened Chinese Restaurant called Gwon Lee’s located at 1635 1/2 East 87th Street, a half-block east of Stony Island Avenue. His wife ran the business following his death.

Cathy graduated from Bowen High school in 1971 and then attended Chicago’s Circle Campus. Her mother and family sold their home, which was located at 8715 S. Clyde Ave., just south of CVS High school and across the street from Stony Island Park, in the mid-70s.

The impact was not as hard for us. Once Stony Island started to change, we could see a change in the customers coming to the restaurants. So we saw the changes a lot earlier than the home changes. The businesses saw the changes first.

One of the good things is that growing up, my parents never differentiated between any races. Their whole focus was that we should get an education and go on to college, and then come out and have a good job.

hat’s all my parents wanted for me.

But they never really gave us those feelings of prejudice. At least I don’t ever recall them. We looked at people as people. They were in a service business that couldn’t distinguish between people or customers.

What I remember was that there was also resistance when we moved in. My parents made the comment that many people who were tried to buy homes from wouldn’t sell to us. Did those people really care because they were leaving. When my dad was looking, a lot of people refused to sell to us. So my dad kept looking and finally came across a home with a For Sale sign. He had a very hard time trying to even see the houses that he wanted to buy. They wouldn’t show it to him. The owners were two elderly ladies who couldn’t keep up the house.

I think that at the beginning, it was a little hard because we were different. We couldn’t hide that fact. We were Asian. Chinese. I don’t recall a lot of outright prejudice. But, I do remember in 8th Grade, Mrs. Langdon reprimanded a student who she heard say something derogatory to m about being Chinese. She reprimanded him in front of the entire class. I felt embarrassed by it, because she put a spotlight on it and made me feel concerned. I remember one teacher advising me that I should be more quiet because I was so loud in my laughter and that I should not be making so much noise so as not to bring so much attention to myself.

Initially there might be some discrimination or feelings, but as time went on, I didn’t see it that often. It wasn’t until later, as an adult, that I really felt the discrimination, on the North Side. I was walking and they were tossing slurs at me as they were driving by. But that was later.

I know my sister is a few years older than me and she had more problems than I did. A lot of the older Jewish kids wouldn’t play with her and she ended up making friends with the non-Jewish kids. I think our generation, our age, was a little different. All of my friends were Jewish and I never felt like I was being left out, intentionally.

We stayed through high school.

The flight of some of the other people made an impression on me after grammar school. I would say that about half of the people who attended grammar school didn’t go to Bowen and just left. They were gone. I was more insulated. All four years, most of my classes were honors. I saw the same kids for the entire four years because of that. I only saw the other students during gym or home room. We maintained a consistent group of friends, classmates.

Our neighbors were Jewish and one night they just moved out and we woke up the next morning and there was another family that was Black that was living next to us. It was such a shock but that is how it happened. It wasn’t that the new family was Black. It was that there was a “new” family and it just happened. Sometimes, you would think living next to someone for so many years, they might at least spend a little time and say good-bye. They didn’t. They were just gone. And that was what was shocking for us.

The change didn’t affect me as much as it did others. I tried to keep in touch with friends like Sharon Zurek and others from Warren Elementary school. High school was a change. We accepted change.

We saw the change coming from out restaurant. The change had come to us a little early and the transition from elementary school to high school prepared us more for change. So for me, it was accepted. We accepted the fact that people were going to leave.

We weren’t going to leave because we had a business.

It was very traumatic the year that King died. That was when we could see changes and people leaving.

We were in school and they told us that King had been killed. I don’t remember whether they told us to leave or whether it was left up to us. But there was a mass exodus. All the cars. Some of the parents coming by to pick us up. There was a traffic jam. There were some of us who said we had to just walk home through the viaduct. I was afraid to walk down 87th Street because we heard there was rioting on 87th Street.

Kids were rampaging down the streets down 87th Street and they did break our window of the restaurant. I stayed at a friend’s house and called my mom, and she told me to stay where I was at, and not to come to the store. She said they were rioting down 87th Street, down Stony Island.

There was a rumor that kids from CVS were coming by us to start a fight.

I remember being with Sharon (Zurek) in the Bowen cafeteria and everything was starting up and all she wanted to do was to bring her bottle in for the deposit. I told her there is a riot going on and all you are concerned about is getting your deposit back. It was one of the bizarre things where the two things were coming together, normal life and the changes that were taking place around us. We all wanted to cling to what was normal for us growing up.

The Jewish influence was very strong on us growing up. I mean, it wasn’t a bad thing. It was just that the large majority of my friends were Jewish and I wanted to be just like them.

I did hang around with a lot of the Jewish kids. They had asked me at one time if I wanted to join the JCC. My brother told me no, we shouldn’t do that. The family vetoed it. It wasn’t that it was bad, because I wanted to be with my friends. But, joining the JCC just to be the same was a little too much. I wanted to join in 6th grade because all my friends joined. But it was different and it was expensive.

But growing up I wanted to be assimilated and to be with them. They used to wear little “initial rings” on their fingers, and then the very thick, gold and silver ID bracelets. I always wanted one of those initial rings. My sister worked at a Jeweler on 87th and then got me a ring and then an ID bracelet with my name on it. We wore the penny loafers. All of them wore the penny loafers and I wanted to, also.

Our life was about wearing the right clothes and the right shoes and buying the right clothes from the right stores. It was a heavy influence on all of us. We wanted to imitate what they were wearing.

Even in Freshman year, there was the BBGs (B’nai B’rith Girls) for girls. There were two sororities and I always wanted to be a part of it. The Jewish boys had their own fraternities, too. Then the YMCA formed some sororities. We formed our own group.

But I remember going with them to their temple and Hebrew school. In sophomore year at Bowen, the school offered Hebrew as a language. At one point, I wanted to take Hebrew and my brother asked me, “What are you going to use Hebrew for?” He was right. I took Spanish, but it was a matter of wanting to be around them and being a part and not being different.

I remember being in High school and saying to family members, “Why couldn’t I be born Jewish.” They said I should be ashamed of myself. You should be proud of what you were.” But it was a matter of wanting to be like your friends. I wanted to be just like them. They didn’t make me feel different at all.

We were different but they accepted me the way I was.

I remember meeting the first Black student at school.

Yolanda Davis was the first Black student that I had met. I only had one class with her.

Jane (Seaberry) and Yolanda always struck me as being very quiet. Jane and Yolanda were, in the beginning, very quiet. That is natural for new students. But I don’t recall that we became very good friends. We didn’t invite them over. They didn’t invite us in. I don’t even know where they lived. It was tough enough just being the new kid on the block, let alone being Black or Asian or Hispanic. We didn’t see difference. We didn’t try to ostracize them. They were just new kids on the block.

I think Yolanda lived west of Stony Island. She was so far away. The fact also was distance between homes. In school, we were all friends. Once outside of school, we went on our ways.

Jeff’s Story:

Jeff lived at 2149 East 90th Street from the time he attended Kindergarten through graduation at Bowen High school in June, 1971.

My family moved out three weeks before my graduation from Bowen High school. I stayed with a friend’s family to complete the final weeks at Bowen, graduating around June 1971. I went to Northern Illinois University. My parents bought a condominium in Skokie.

The bottom line is that the neighborhood was the ideal neighborhood. It was full of baby boomers, lots of families with children. They were all good people, good working people. Middle Class. They strive for a good education. The parents had experienced the Depression and that was an influence on them. Perhaps, that had to do with the flight.

There were great parks, a great school system. Every year, a team of Bowen students would compete in that TV show — I think it was called “It’s Academic” — with the student teams. Bowen would always win.

We had a large Jewish community, a very strong community. I think the Jewish community made up more than 40 percent of the population, possibly more. Considering that we (Jewish community) are only 2 percent of the entire country’s population, our community was significant as a middle to upper middle class Jewish community.

The change just happened. I don’t think that my parents or my neighbors were really prejudiced against Blacks. But, I think they were more concerned about the economics. Slowly, but surely people left. People started moving north, to the Mather High school area, or to Skokie. A lot of people I knew moved to the North Suburbs. Then, people started to go south to places like Flossmor and Glenwood.

Today, whenever you hear “Where’d you grow up” and you hear the answer “South Side,” it’s almost like we have something special together. We were all there in our youth which was an important time in our lives.

By the time my family had left, Bowen High school was probably half Black, or more. And that was a significant change from when we started as freshmen. It was about 25 percent Puerto Rican and maybe 8 percent Jewish and 10-12 percent when we left around 1971. The Polish community was really resistant to leaving. They refused to move out of their community, and that determination remained very significant. As people were moving out, more and more of my friends were non-Jewish, Polish. We had Black and Hispanic friends, too.

Unfortunately, toward the end, people started moving for other reasons besides economics. They were moving because they really started to sense a change in the neighborhood, not just because Black people and other people were moving in. But a sense that we weren’t safe anymore. And events fed into that growing feeling, especially at Bowen High school.

I remember someone walking right into the Bowen cafeteria during our senior year and spraying the cafeteria with a shotgun. That is something that had never happened before, but was a reflection of the crime that was increasing in the area.

Our educational system seemed to drop. We were no longer the leader in education. That image or perception was gone. And, I was finding that the education I was receiving at Bowen was actually inferior to the education some of my friends were receiving at newer high schools in the suburbs where they moved. But as far as being streetwise, I was superior, because I learned how to work with other ethnic and racial minority groups. That can be just as important and it had an impact on me as I got older.

As an adult, when I chose a place to live, my first thought was to move to Evanston because Evanston had this image as a mixed neighborhood. I thought that was good, what I wanted. But even in Evanston, a lot of my friends would put their kids in private schools at the high school because of some gangs there, like the El Rukns.

I kind of liked a mixed neighborhood like Evanston. I have three children and my concern is for them.

When I went to Bowen, I remember three Puerto Rican students who jumped me. I came out the wrong side of Bowen, one day, with our friend, Mike Rothman. This Puerto Rican guy had this cane, like a blind man’s cane. I knew he wasn’t blind but he walked right into me. The other two jumped on me. They held me and threw about 100 punches at me. I blocked all 100 punches, but unfortunately 90 were with my face.

My wife went to high school in South Shore where she lived. The changes there started a little before our area. She got jumped when she went to South Shore, and I will tell you that is a defining moment for people. It shouldn’t happen. We started seeing that kind of conflict happening and that wasn’t good. People started associating that kind of problem with “change.” My wife got jumped by some Black kids at her school. She had a doctor give her a note, after it happened, saying that she couldn’t go back to school there because of nerves. She left South Shore High school and finished at Bowen. She was one of maybe 60 White students left at South Shore high school. We met at Bowen, and then attended the same college together at Northern Illinois University.

The transition from White to Black happened over a three year period, so it was pretty quick. But it just became a part of your life. You lost friends and made knew friends while it was happening. And, then, toward the end, we had very few friends left.

We didn’t participate in things like the Prom. The Prom was more of an anticipated gang fight. My friends didn’t go because we thought that several of the gangs were looking forward to fight. It was always rumored that there was going to be a fight, so we stayed away. The only Jewish kid I knew who attended went there with his chains to fight.

Tensions were high.

The King Riots in 1968 is something I remember vividly. There was a riot at Bowen. I ran home with a good friend of mine who was Black, Charlie B. After two blocks, I stopped him and asked him why we were running. If someone hassles us who is White, I reasoned, I would tell him that he (Charlie) was cool. If the person was Black, he would tell him I was cool. Charlie turned around and said to me, “If you have 25 cents in your pocket, the boys from CVS don’t care what race you are.”

We continued running home.

Many of the Blacks who were actively involved in athletics were really nice to be around. It seemed they were focused on the sport. That was something we could share together. So, we got along. The ones who weren’t involved in sports and who seemed to be poorer, kept hitting on us for money. If you showed you were afraid, they’d continue to pick on you. If they demanded that you give them a quarter and you gave it to them, they’d keep hitting on you. If you stood up to it, they seemed to leave you alone.

When we were kids, we’d get into fights. But it seemed that the fights only reached a level of fists. Sometimes, the Puerto Rican gangs had knives, but that was somewhat rare, at first. Then, it turned to knives and guns and that changed things. Nowadays, every street gang member has a gun. We used to fight with each other and still be able to walk away. It didn’t seem like that was going to happen as things changed.

Midnight Flight

Chapter 3: A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

Chapter 4: Written Long Before

Chapter 6: Alone in the Playground

Chapter 8: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 10: The Sub-Urban Life

Chapter 11: Friends Left Behind

Chapter 13: Notes from Readers