![]()

Midnight Flight: Chapter 2, Dividing Lines

One family’s experience of White Flight and the racial transformation of Chicago’s South Side (an online novel)

By Ray Hanania

Midnight Flight, (C) 1990-2020 Ray Hanania, All Rights Reserved

“You never really knew a man

until you stood in his shoes

and walked around in them.”

— To Kill a Mockingbird

When I try to remember the old neighborhood, the towering trees are what I miss most. They formed a tunnel of leaves over the street, something that remains till this day.

It is a cherished memory but a small part of what was left behind when my family abandoned our Chicago home to begin a flight that led us to a new home and surroundings in what we came to know for the first time as “the suburbs.” The move in October 1968 was the beginning of a long journey for us as racial tensions and fears continued to escalate on Chicago’s South Side.

It began as “White Flight.” But it quickly turned into an excuse to redefine the pursuit of the more perfect “American dream.”

Left behind were the tall, beautiful, full trees, rustling in the light breeze overhead. Providing a real sense of comfort and belonging — roots – the trees finished the picture of what a great neighborhood should be like.

My father was modern in some ways but Old World in many others. He wasn’t Fred McMurray and didn’t talk much with us about social issues at the dinner table, or anyplace else for that matter. But somehow, the perceptions of problems that haunted our family and the neighborhood just seemed to be communicated from one person to another.

Dad was always serious. He was consumed with the struggle to earn enough money to feed, cloth and house his family. He wasn’t a young father, like the fathers of many of my friends. Dad had remarried late in life. He was in his 50s when I was born, although I am not sure what year he was born in. My mother was many years younger, and I was closer to her. But at my birth, she had only been in this country less than 9 months and was still struggling with the English language. That’s how I got my name, Raymond. In the hospital after giving birth, mom could only understand one phrase that she heard over and over again on the loudspeakers above her head. “Doctor Raymond. Doctor Raymond. Doctor Raymond.”

It’s every Arab mother’s dream, to have their son grow up to be a doctor or a grocery store owner. Fortunately, my father managed to get her to drop the word “Doctor” from the birth certificate.

I don’t ever recall dad waxing poetic about the need to leave our Chicago neighborhood in South Shore Valley to find a better place to live in the tree-less suburbs. I had never even heard of the word “suburbs” before, and it was anew term in the American lexicon. That all just added to the eventual shock we experienced when we did move.

His most important concerns involved economics — his small savings account, building a small college fund for his three children, and strengthening the equity in his home.

The goal of living in the suburbs was not everyone’s idea of the American Dream and it was far from being my father’s own dream. It didn’t make sense, either. Why would anyone move so far away from the center of the city where you earned your living? My father worked in downtown Chicago, “the Loop.” There was no transportation in the suburbs. The relatives didn’t live there. It was time consuming to travel from there. And, it was strange.

We already found what had amounted for us to be the American Dream. It was in our cozy, two-bedroom, two-story light brown speckled brick Georgian on a street lined with tall and sturdy Maple trees, small but lush green lawns, and white painted picket fences low enough so that you could reach across the pickets and shake the hands of your neighbors.

What was more American than that?

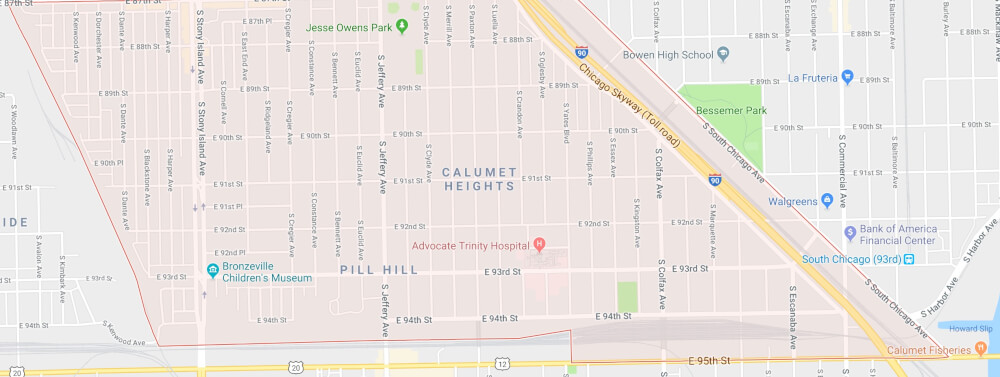

Our bright red 1963 Rambler parked in front of our home wasn’t a luxury car by any means, but it was comfortable. Dad had traded in a 1959 gray and black Plymouth with a push-button gear shift. The new Rambler was something we were proud to own. The Cadillacs and Mark II’s were parked in driveways of homes on the west side of Jeffery Boulevard in Pill Hill. Sure those cars looked beautiful and luxurious. But our Rambler was parked among other middle class cars. Plymouths. Chevrolets. Chryslers.

Buying a new car was a big deal. When dad drove the Rambler home from the dealership, everyone on the block came out to take a look and run their hands along the high polished red finish. The fact that it was an inexpensive car didn’t matter. It glowed with everything that we and the rest of the neighbors wanted in life.

We didn’t sit there envious of Pill Hill and its wealth, but we did respect the fact that the nearby community only added value to our own homes and our community. We seemed content with what we had. And I am sure my father was content knowing that the value added in his home was a financial investment he could count on in the future.

Each morning, mom would make breakfast and put the gray fedora on dad’s head as he headed out the door to board the rush hour bus on Jeffery Boulevard a few blocks away. Jeffery Boulevard was our transportation lifeline to the Chicago Loop. Communities were built around such transportation points. In the late afternoon, I and my sister would sit on the front stoop at a stranger’s home on 89th Street and watch and wait for my father to step off of the South Bound bus returning him and other fathers home from the Loop jobs. The fact that we didn’t know the owners of the home didn’t matter at all. No one would bother us. That’s the security sense of the neighborhood we all shared back then.

When we’d see him walking home from the bus stop, we’d run up and jump into his arms. Fathers were doing that everywhere in South Shore Valley.

We also attended a good elementary school and looked forward to attending a highly rated high school, Bowen, when we graduated. It was one of the reasons my parents felt so comfortable about the area.

My sister, my brother and I would eat our cereal, and then make sure our sandwiches were wrapped tightly in wax paper, tucked neatly into our lunch boxes. Mine had a picture of Roy Rogers on the front.

We were off to school in no time.

It was a neighborhood school. Joseph Warren Elementary school was located at the top of the hill at 92nd and Jeffery Boulevard. We walked there. Seven blocks in the morning and seven blocks on the way home. There was no bussing plan to integrate the neighborhood schools. I walked passed familiar places, including the homes of my friends on my way to school. I was very close with my friends, even though there were many things that kept us apart.

Bethany Lutheran Church is located north, across 92nd street, from Joseph Warren. It’s still there, with a Black congregation, today. That’s where we went on Sunday mornings for church services. It was a simple but sturdy looking structure with wide sidewalks, expansive front lawn leading to a large entrance facing the community. Christian churches love to have their congregations gather and linger in the front, and enter together. Our pastor, Roy Ryden, lived in the adjacent home. My Jewish friends went to the larger, more elegant Rodfei Shalom Synagogue one block north. The entrance was right up to the sidewalk, but the Synagogue was as large as our elementary school. It housed a Hebrew School. The outdoor play area was fenced in.

We respected the boundaries of our neighborhood, too. Out of fear, and maybe a little bit out of selfishness. Or maybe, it was just that we didn’t really know or care about what was beyond our neighborhood.

We rarely went beyond the viaduct on the east. Beyond it was South Chicago Avenue and Commercial Avenue. We didn’t cross 87th Street on the north, even though across 87th Street was Chicago Vocational High school’s (CVS) vast baseball and football fields. We rarely crossed the viaduct on the south, which ran parallel to 95th Street and entered into a whole new area called Jeffery Manor.

And, we didn’t cross Stony Island Avenue, to the west, unless we had too. There was a certain irony about how the streets were “designated.” For example, Jeffery Boulevard was really just a two-lane street. Stony Island Avenue was a beautiful, multi-lane boulevard. Jeffery Boulevard belonged to “us,” and Stony Island Avenue was shared with “them.” Even the selection of the names seemed to reflect differences. One of the few times I crossed Stony Island Avenue was to go to the Chicago Public Library branch that was located on the west side of the avenue. My mother had to drive me there. I could walk up to the east side of Stony Island, but not cross it.

Stony Island Avenue was a “dividing line” between the White, predominantly Jewish community on the east, and the growing Black community on the west. We knew they were there. We just didn’t see them that often, at least at first. Or, maybe we just didn’t look for them.

The jewel of South Shore Valley was Pill Hill, nestled tightly between Jeffery Boulevard and Stony Island Avenue. It was a predominantly Jewish enclave of fashionably built homes anchored around Rodfei Shalom Synagogue. Across the street, was the Henry N. Hart Jewish Community Center. In 1959 the Henry N. Hart JCC opened in the Calumet Heights area in the southern part of the city at 91st and Jeffery Blvd. The Henry N. Hart name was later transferred in 1971, however, to the JCC located at 2961 West Peterson on the North Side of Chicago when the center on 91st and Jeffery Blvd. was closed and the Jewish community moved north.) Next door was Mel Markon’s deli.

Some time in the mid-60s, the JCC added a large outdoor swimming pool for its members that fronted on Jeffery Blvd. I went there often as a guest with my friends.

Pill Hill got its name from two factors. The first being that many of the Jewish fathers living there were doctors. Pill Hill enjoyed a reputation that was far greater than the reality. But a few streets, like Bennett Avenue from 90th to 92nd Street, showcased South Shore Valley’s most spectacular homes. Jewish doctors owned all four of the homes located at the intersection at 92nd and Bennett. Their children had been my classmates in school. Although it had many doctors and lawyers, for the most part, the homes on the other streets in Pill Hill were very similar to the homes on the east side of Jeffery Avenue where I lived.

The second reason for its name was actually geographical. A hill divided South Shore Valley, a limestone ridge that ran along 91st Street through 92nd Street, the top of the hill. The best homes were built along this inclining street slope adding an extra luster to the already beautiful area.

Between all of this was the heart of South Shore Valley, a mix of middle class Jews, a few Arab immigrant families, and white collar Whites. (It was also called Calumet Heights, which is the name that later stuck). The fathers worked downtown at banks like Northern Trust, or the corporate offices of international oil companies like Sinclair and Standard Oil. One of Standard Oil’s key executive, Ken Morrow, lived next door with his wife Dolores. I would babysit for their son Glenn, who was named after the Astronaut. East of Yates were many Eastern European families, whose fathers worked at the Steel Mills.

Just south of Warren Elementary school was a poorer, blue collar Christian community, consisting mostly of frame homes and the area’s harvest of “greasers.” Most of the Jewish students aspired to go to Bowen. That’s where I wanted to go. Most of the “greasers” looked forward to a technical education at Chicago Vocational High school, located on 87th Street. I only knew one Jewish student who went to CVS after graduation from Bowen. All our friends said his grades weren’t that good. Students went to CVS because of poor grades. That was the perception. Despite that, my brother, who had an excellent academic record, went to CVS where he graduated and continued on through college to become an engineer. And there were many other schools nearby including Caldwell Elementary and Hoyne Elementary.

These were the kind of social choices that confronted our community, the kind of choices we didn’t mind facing.

The viaduct on the east divided the communities racially and economically. It was the last barrier of several barriers that kept the Mexicans and Puerto Ricans apart from the Serbians, Croatians and Poles, separating all of them from the “rest of us.”

These neighborhoods were far from being melting pots. We were clumps of diversity floating in Chicago’s pottage of ethnic “mix.”

As we got older, the boundaries remained, but we would take excursions on Saturday or on holidays to the Oriental Theater in the Loop to see the James Bond movie, Goldfinger. For 12 and a half cents, we took the Jeffery Boulevard bus downtown. We played the pinball games at Treasure Island. We sat and ate Wimpy hamburgers across the street from the Art Institute. We were only 12 and 13 at the time.

Then we went home.

If we had to go to the Avalon Theater, north of 87th Street, our parents would drive us there and then pick us up when the movie was over. There were all kinds of silly movies that we watched starring Doris Day, Cary Grant, Rock Hudson, Fred McMurray and Dick Van Dyke.

Avalon was a different neighborhood. The concerns weren’t dramatic, but they were there.

We walked around them when we couldn’t avoid them.

Nobody had told us that “different” also meant “scary” or “dangerous.” But “different” did raise our guard and there was a sense of fear when we were someplace else.

We had all heard the ghost stories at summer camp or in the Cub Scouts. And, we had heard the tales about the “boogie-man” and the “hatchet man.” We knew that dangers lurked beyond the boundaries of our neighborhood, across the “dividing lines.” No one ever spelled out what those dangers were, but we knew they were there. And it had to do with things that were “different.”

The fears lurked in the “darkness.”

And, if that were not enough to feed the fear of something being “different,” there was the television set which was filled with an assortment of programs providing very subtle messages about who was good and who was bad.

We didn’t have to get off the bus until we got to the Theater, watching instead with curiosity as we passed through strange neighborhoods filled with strange looking homes and people. We were glad we didn’t live there.

Halloween was a good example of the high comfort level that existed in South Shore Valley during the late 50s and 60s. Young children were permitted to go out on their own late into the evening, after the sun had set and the street lights had gone on.

Our neighborhood was safe. And the only fears of a razor blade being plunged into a Halloween apple were those fears expressed among us kids, mostly trying to frighten each other.

We could walk from house to house and knock on doors and the neighbors several blocks away would know our names. That comes not from structured social guidelines, but from a high comfort level in a neighborhood where people went out of their way to get to know each other.

We took it for granted, also, that the teachers who taught us during the school year also lived right in our neighborhood too. I recall the fear of knocking at the door of one teacher who lived at the corner of 90th and Merrill Avenue. She always made caramel corn balls and hand wrapped them in colored sheets of cellophane. It was always the highlight of Halloween. Even through our masks, she would recognize her social studies students.

South Shore Valley boasted a wonderful familiarity and friendliness. That encouraged security and confidence.

But like the huge trees, that, too, was missing from the aseptic suburbs where we later found ourselves, refugees from a racial skirmish, a social war that we had no control to stop.

The 50s and the 60s were rough decades. They represented continued change. Decades of upheaval. Decades when racial issues began to seep beyond the headlines and slowly make their way into our lives.

I didn’t know of any “Colored” kids my age. They weren’t called “Black,” back then, they were called “Colored.” Today, though, that would be considered derogatory. I guess the fact that we referred to any other people by their skin color was probably derogatory by nature. But it was done.

I had seen a few Black people riding on the bus, and saw a few working in our neighborhood. There was an elderly Black maintenance man at the Rodfei Shalom Synagogue. The commercial strip along 87th Street between Luella and Stony Island Avenue was a magnet for shoppers from our area. It was rare to even see Black people crossing over, although there were a few celebrities who were exceptions.

As a child, I had heard about “Colored people” on the TV news. They didn’t seem to exist on TV sitcoms like My Three Sons, which was a cookie-cutter for White society. Black people worked as janitors and as maintenance workers at some of the local businesses. Not at our school, though. Not at the church we attended every Sunday. Not at the restaurants we ate at.

My image or perception of them was not very high, a feeling shared by many. I guess the essence of racism or racially inspired fear is that it is easy to hate someone whom you do not hold in high esteem.

The apparent absence of Black people and families seemed to connect to our comfort level as a community. Race differences didn’t seem that important when we were dealing with other ethnic groups. Greeks, Poles, Serbians, Arabs, Asians and Jews all had differences but those differences were accepted, or at least not challenged. Maybe, the differences were even ignored.

My parents never spoke unkindly of Blacks, Hispanics. (There was no such term as “Hispanics,” either. They were Mexican or Puerto Rican. Or, just Spanish.) My parents never spoke disrespectfully of other ethnic groups, either. After all, we were Palestinian Arab and our skin color was slightly darker than the rest, too. It was olive colored. Yet, we were not called “colored” as were Black people. Obviously, the racial feelings had more to do with other social issues than they did simply with skin color.

We lived in a predominantly Jewish community, too, yet everyone seemed to live together without the ugliness of racism. Being Palestinian Arab, that could have caused a problem, too. But it did not. Most of my friends were Jewish. But our differences never became an issue, and my parents never spoke unkindly about Jews, either.

When the Arab-Jewish issue was right in your face, however, sure it surfaced. After the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, for example, some of my friends convinced me to dress up in real Arab Bedouin clothing, a Keffiyeh on my head and long robe with a scimitar at my side. Larry Kogan and I knocked on doors in Pill Hill that Halloween. There were only a few homes where people who answered the door simply threw the candy at us before we actually got to their front doors to knock or ring the door-bell. I’m not sure they were trying to hit me in an Arab outfit or Larry, my friend, who was also well known to other kids from some of the families there.

At least they threw chunky Baby Ruth bars, though, and not tiny candy corns.

It seemed that the richer an area, the better the candy. Pill Hill was a treasure of expensive candy bars. Toward the east side of South Shore Valley, the home owners would open small bags of orange and white stripe “candy corn” and count out five pieces that they dropped in your bag. Those homes got egged very quickly.

For a long time, race just didn’t seem to be an issue, although it really was.

The bubble seemed intact. Until one day, a “Colored” student, Lee Bogan, registered at Joseph Warren Elementary school. Three more Black students, Jane Seaberry, Yolanda Davis and Michele Demby, followed. I’m sure they owned homes in or near our neighborhood, but at first, it didn’t seem to set off sirens. The barrier was broken at the school level, and it forced parents to start thinking about the bigger picture. Attending our schools pushed the threshold. Moving into our neighborhoods, on our blocks, crossed the threshold.

In 1968, the year after graduation from elementary school, that second threshold or barrier was broken. Several Black families moved into homes on our side of Jeffery Boulevard. One of those families moved into a home on our block on Luella Avenue, several houses from my own. And, as suddenly as the Black family moved in, the entire neighborhood seemed to panic and White families began to leave. “Began” is too soft of a description. They ran. They packed up their belongings in a disorganized panic and they fled.

The family that moved near us had two children, a young boy, and an older girl who was handicapped and who seemed to maneuver her wheel-chair up and down the block all day, her head leaning to one side. Her speech was slurred, but understandable.

They didn’t stay long. A friend of mine who lived on my block and I went up to meet her. She seemed to be a nice person, although her handicapped speech was pronounced.

The racial rumors were rampant. But as hard as I tried, and in talking with other friends who lived nearby, no one could place a finger on the exact moment when the racial bubble burst. But it happened. Just that quickly.

There were secret meetings up and down the block in the basements of several of the homes. People were called to attend deliberately, quietly and somberly.

“We have a meeting tonight to talk about the problem,” the caller would whisper. “It’s at Stuart’s home. 7 p.m.”

It was just called “The problem.”

Everyone was mad at the family that had “sold” their home to “those Colored people.” As it later turned out, the Black family was only renting the home. No one knew how long they would stay. That didn’t seem to matter. The fact was they were there. And, their leaving was not going to change anything one bit.

Realtors started knocking on doors, like vultures feeding on the remains of the neighborhood’s fears. They could smell the “neighborhood death” that was all around us.

“If you don’t sell now, you’re never going to be able to sell and you will lose all the equity that you have built up in it.” Real estate agents brought it down to a level neighborhood fear could understand: “You don’t want to lose your home, do you?”

Race was about economics as much as it was about societal differences. Of course, if no one moved, there wouldn’t be an issue of plummeting home values.

In 1968, things changed in South Shore Valley. Our block at 89th and Luella Avenue was part of the fuse for an explosion in race relations that transformed the community and sparked a White Flight surge out of South Shore Valley. The world was exploding around us and it was hard to tell which explosion was which any more. Assassinations. Riots. Racial turmoil. All of it served as a backdrop for our own growing tensions.

There could have been a natural integration. One based on slow change. People who moved in could have replaced people who were moving out for other reasons than race. That small group, unfortunately, will forever bear the scars of White Flight only because of coincidence.

The fear that many White homeowners experienced may not be justifiable, but nonetheless, it existed and was real. And the stampede that it caused can be compared to the stampeding of cattle. White Flight stems from a communal-based fear or a herd mentality, something similar to what cattle experience as the frenzy toward stampede takeovers.

Like a stampede, White Flight relies on a bizarre kind of trust.

One cow or several cows on the fringe of the herd are frightened into running. Their fright is absorbed one cow to another on the basis of trust. The other cows, not having seen the cause of the original fear, accept the fear as fact. They react as if they had seen the cause of the fear without confirming it. This spreads like a shock-wave through the herd, or, in this case, it spread through the White community.

In less than a year, more than half of the homeowners had put their homes up for sale and were making plans to move to suburban locations “that would remain White for decades to come.” Most of them probably didn’t understand the reasons why they were moving, and just wanted not to be the last ones left behind, living in homes that had no value and in communities destined to deteriorate and rot.

If no one cared about who they lived among before, it mattered that year. The Jews moved north to growing “Jewish” communities like Skokie, Niles, and south to communities like Flossmor. Most of the Catholics moved west to strong “Catholic Parishes” while other non-Catholic Christians moved east into Hegewisch.

That summer in 1968, South Shore Valley had lost its innocence.

Looking back, I realize now that the Black families that moved in buying up the de-valued, under-priced homes in the White Flight Fire Sales were not the ones who destroyed that community.

The existing community was destroyed by the people who fled, not by the people who came. Those that left were too willing to give up so many years of contentment and satisfaction.

Certainly real estate panic-peddlers were very much to blame. But the panic was almost irrational, especially when you look back at it from our time, today.

We didn’t run from Black families. They were looking for the same neighborhood values that we had and had wanted for ourselves. We ran from our own self-inflicted nightmares.

More tragically, we didn’t leave looking for something better. We left fleeing from something we feared and didn’t understand. We knew what we thought we were running from, but we didn’t know where we were running to.

South Shore Valley was a community of people turning the corner into the turbulent decade of the 1970s afraid of the shadows they thought they saw.

All someone had to do was yell “boo!”

Midnight Flight

Chapter 3: A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

Chapter 4: Written Long Before

Chapter 6: Alone in the Playground

Chapter 8: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 10: The Sub-Urban Life

Chapter 11: Friends Left Behind

Chapter 13: Notes from Readers

Comment on “Midnight Flight: Chapter 2, Dividing Lines”