![]()

Midnight Flight: Chapter 8 — In the Eye of the Storm

One family’s experience of White Flight and the racial transformation of Chicago’s South Side (an online novel)

By Ray Hanania

Midnight Flight, (C) 1990-2018 Ray Hanania, All Rights Reserved

“I can fly like a bird in the sky.

“I can buy anything that money can buy.

“I can turn a river into a raging fire.

“I can live forever, if I so desire.”

— I Can’t Get Next to You, The Temptations, 1969

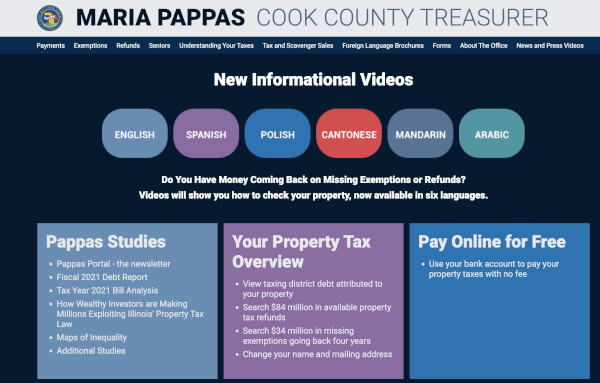

The role that Realtors played in the panic-peddling and the break-up of South Shore Valley in the fall of 1968 did not become immediately apparent.

These real estate agents came from outside of our community, from other predominantly White areas where they wouldn’t think of committing the same practices on themselves. South Shore Valley and South Shore Gardens were red-lined by the Realtors. These real estate agents were feverishly making telephone calls, as if they were losing a dollar for every minute they weren’t on the telephone telling some White homeowner how the values of their treasured homes were about to come crashing down. They were knocking on the doors of White homeowners and handing out literature addressing the “economics” of the home values in the area. They stressed the availability of low-interest mortgage rates of around 4.5 percent. It almost seemed as if they feared that if they didn’t sign “us,” another competitor might sign us instead. And that, to them, meant lost sales commissions.

We weren’t just a “White” neighborhood. We were sheep being led to the slaughter. And we followed willingly.

To the Realtors who savaged our neighborhood, South Shore Valley was a gold mine ready to be harvested of profits.

Home rented to the first Black family that moved into the neighborhood on 89th and Luella in 1968.Many families at first viewed the Realtors, who were always very calm and who seemed to always smile, as providing a needed service. What that “needed service” was didn’t become apparent for most unsuspecting families until many years later. “Panic-peddling” was a term that was coined after-the-fact, not during. It was a label used in other communities that witnessed what was starting to happen in ours. It resulted in the formation of block clubs, groups of organized homeowners who worked together to prevent their neighborhoods from “changing.”

Once the East Side transformed, the “dividing line” moved west. In 1970, it was Halsted Street. Then it was Ashland Avenue where Father Lawler organized a high-profile effort to keep the area white. Then it moved further west to Damen Avenue, then Western Avenue. And that is where the dramatic confrontations between the “Bogan Broads” and pro-bussing advocates made their last stands.

High interest rates that peaked at 16 percent and 17 percent in the mid-70s slowed the White Flight down until it almost stopped. White municipal workers who held jobs with the City of Chicago and who were bound by residency laws requiring them to live within the city, crowded into neighborhood pockets in the farthest reaches of the city. With no place else to go, the panic selling seemed to stop, briefly, in areas on the furthest ends of the Northwest and Southwest Sides. Some people bound by the city’s residency laws, purchased homes in the suburbs, trying to live dual lives. Suddenly, the economics of a job held by a fireman or a policeman or by a well-paid city employee became more important than the economics of the home values.

Now, White homeowners, supported by local politicians were willing to stop the flight and draw a permanent line. But that was looking into the future. And in 1968, White Flight seemed to be the by-product of the heightened awareness of racial differences, partly because of the activism of the Civil Rights movement, and it only fed more hatred.

Unless you had already experienced block-busting, you could not recognize the signs. But the signs were all around us. We were just too blind by fear to see them or to react rationally. What occurred was not rational, although it was very human and very much predictable.

First there was a Black student at our grammar school, several years before. Then three more. And now, one of the neighbors just packed up his family, literally in the middle of the night, and moved out and a Black family had moved in their place.

There had been a few good-byes the night before between the eldest son, my brother and a few others, but I think there was an expectation that a family leaving the hub of such a close knit group might have made a little bigger deal about leaving.

The following morning, when moving vans arrived to unload the furniture and belongings of the new family, I noticed that the neighborhood had changed a bit.

Families were on their front steps watching as the new family drove their car to the curb and parked in front of their new home, behind the moving van that was being loaded.

The father got out first and walked around to the other side of his car, opening the door for his wife.

They were Black.

They looked like the rest of us. Same clothes. Same car. Same mannerisms.

Except that they were Black.

They had two children, a young boy and an older girl who had to be helped out of the car and placed in a wheel chair.

She was retarded.

It was a very clever move on the part of the Realtors.

The family that moved in had rented the property, probably from the Realtors who purchased it from the prior White owners. I don’t know what the legal arrangement was. Nobody really knew. There was just a lot of neighborhood talk. But this new family only stayed for about six or eight months, just long enough for the irrationally fearful neighbors to sell their homes, too. Probably through the same Realtors who might have been involved in the rental of the first home.

As the neighborhood buzzed about the presence of Black students at local elementary schools, the presence of a Black family solidified the intentions of many.

There never was a chance for the two sides to come together and understand what was really going on at that moment.

Black families moved in looking for the same things that had attracted the original White families who came to South Shore Valley. They wanted a safe and secure community where they could raise their children. They wanted a good home, and good neighbors. They wanted their children to attend good schools. They wanted a decent library. Good grocery stores. They wanted to see their homes increase in value through care and proper maintenance.

But those parallel needs were overshadowed by the needs of Realtors who recognized that most White homeowners were easily frightened, and who could be easily motivated to place their homes for public sale.

Midnight Flight

Chapter 3: A Beautiful, Idyllic Community

Chapter 4: Written Long Before

Chapter 6: Alone in the Playground

Chapter 8: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 10: The Sub-Urban Life

Chapter 11: Friends Left Behind

Chapter 13: Notes from Readers